After failing to entice Connery back for another film, producers Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman were faced with recasting 007 for the third time in four years. Julian Glover, John Gavin, Jeremy Brett, Simon Oates, John Ronane, and William Gaunt were tested but the main frontrunner for the role was Michael Billington. At the request of United Artists, who feared that no unknown could replace Connery successfully, the producers also explored some huge American stars as a possible new Bond. Clint Eastwood, Paul Newman, Robert Redford and Burt Reynolds were all either offered or considered for the role.

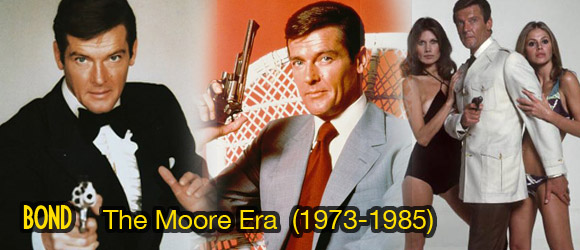

Through all the years they had been making the Bond pictures, another actor’s name kept coming up when the task of casting came up. He knew the producers personally, had always been a desired candidate, but timing had always gotten in the way. He was famous and wealthy for his 7 year run as Simon Templar in The Saint, and in 1972 was the highest paid TV actor in the world for a one year run on The Persuaders. Roger Moore, as fortune would have it, was finally available to become James Bond.

After a tumultuous period trying to re-establish the series, Broccoli and Saltzman had a leading man that was very sure of himself and the approach he would take for the character. He would avoid entirely Connery’s incarnation, instead playing to his own strengths. Moore was much older—45—than any other Bond at the beginning of their tenure. He did not have the same raw physicality as Connery or Lazenby, but what he did have was suaveness, assuredness, seasoning, and that would transform the Bond of the Seventies and early Eighties into more of a lethal comedienne.

Live and Let Die would introduce the world to Moore’s Bond, right in the thick of the Blaxploitation era. Taking some heavy cues from that style of film, this adventure would pit Bond against some African American adversaries and explore certain aspects of New Orleans, especially its connection to the occult. Very quickly, Moore’s Bond lets you know he’s a different kind of animal, with his quips and raised eyebrow a far more likely reaction to his enemies than the brutality of his predecessors. His choice of drink, his choice of smoke, his choice of dress—all deliberately different; Moore was running his own race from the outset.

Moore still to this day is the longest serving Bond, so it may surprise to know that his debut was not as well received as the nostalgia that honours him today. Live and Let Die was given mixed reviews at best, with many commenting the film was as crass and clichéd as the Blaxploitation films of the time. Clifton James’ character Sheriff Pepper, who would return in the following film, was viewed as one step too far into the comedic. This film sought to embrace the outlandish aspects of Bond’s world, and present a leading man that was willing to go along with it. When Live and Let Die finished its theatrical run, it had out-grossed Connery’s last entry by nearly 50 million dollars. Was it purely interest in what yet another actor in the role would be like?

Moore still to this day is the longest serving Bond, so it may surprise to know that his debut was not as well received as the nostalgia that honours him today. Live and Let Die was given mixed reviews at best, with many commenting the film was as crass and clichéd as the Blaxploitation films of the time. Clifton James’ character Sheriff Pepper, who would return in the following film, was viewed as one step too far into the comedic. This film sought to embrace the outlandish aspects of Bond’s world, and present a leading man that was willing to go along with it. When Live and Let Die finished its theatrical run, it had out-grossed Connery’s last entry by nearly 50 million dollars. Was it purely interest in what yet another actor in the role would be like?

The Man with the Golden Gun would attempt relevance by commenting on the energy crisis of the time, and the interest in Eastern martial arts that was growing rapidly. Christopher Lee was cast as Bond’s adversary, Scaramanga, and would end up being one of the only things praised from the production. 1974 would see Bond’s box office at a new low—only 97 million—with critics and the public disliking the more comedic tone the series was taking. This would also be the first of three Moore era movies that Bond girl Maud Adams would star in. And this would be the last Bond film Harry Saltzman would be involved in; with his wife’s health ailing and financial problems, the founding producer would sell his 50% stake in Bond, leaving Cubby Broccoli to go things alone. This would also be the last film Guy Hamilton would direct for the series. All in all, the future was again looking uncertain. It was up to Broccoli to turn things around.

Bond’s next adventure would have to impress like none had in the 1970s. But as production began for The Spy Who Loved Me, Broccoli was faced with hurdle after hurdle. Guy Hamilton left to film Superman (something he didn’t end up doing) and finding a replacement was taking too much time—Spielberg was also on the producer’s radar for this one—the script was taking too long to find its tone, and the Kevin McClory problems started again, preventing Eon from using the character of Blofeld or his organization SPECTRE.

You Only Live Twice director Lewis Gilbert eventually stepped into the director’s chair, and he brought with him a new writer, Christopher Wood, who wanted to jettison the more slapstick elements of Moore's previous two films and steer the film closer toward the Bond of the novels. Blofeld and SPECTRE were omitted, to save the production from being bogged down in legal battles, and a more traditional Bond adventure was set to go.

If Moore’s tenure had been a little shaky out of the gate, it was about to become a whole lot more stable. This film is regarded by many, including Moore himself, to be the best of the Moore era; its spectacle was, at the time, unparalleled and led to the creation of the 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios—there simply wasn’t a stage large enough for the jaw dropping Ken Adams’ set. This would mark the first time we would see Richard Kiel’s towering menace, Jaws; and it would be the first time Fleming’s name would be shifted from above the title to above Bond’s name. Crowd’s flocked in their droves to see the new adventure, and, considering it came out only a month after Star Wars, there was no question anymore: Broccoli had turned things around. 185 million dollars later, The Spy Who Loved Me basked in glowing reviews and with a script that finally tailored things specifically for him, Moore’s Bond was primed for another adventure.

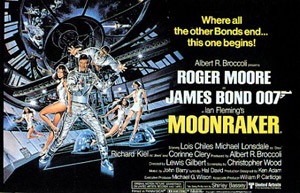

After Star Wars had blitzed box office records, every studio and producer in the business wanted something with space in it. Broccoli, ever the shrewd businessman, was no different, and even thought The Spy Who Loved Me had proclaimed that Bond would return in For Your Eyes Only, Moonraker was chosen as the next film. This would be the first film beyond Roger Moore’s initial three picture contract, and would start a four time renegotiation for the actor to return to the role. Jaws, who proved popular with children, was returned for another go around with Bond, only this time transformed from adversary to ally throughout the film; it would also employ arguably the series’ most risqué Bond girl name in one Miss Holly Goodhead; and Bond would go into space, facing an outlandish villain’s space base and laser guns, to save the day. History deems this as the most camp of Moore’s entries and the series in total, and contemporary reviews were mixed, with some saying it was the best one since Goldfinger and others trashing it completely. It was the most expensive Bond film made by a long stride at the time, costing 34 million to produce, and, when it took 210 million at the box office, out-earned any Bond film by leaps and bounds—a feat not beaten until Goldeneye in 1995. Moonraker remains one of the most divisive Bond films in the Eon canon, but no one can argue that the final Bond film of the Seventies took Bond out on a high.

As the Eighties dawned, the edict for this new decade was to bring Bond back to basics. With Moonraker’s excesses, it was felt to pursue that approach any further would be a slippery slope indeed. John Glen, another long time Bond editor, took the director’s reigns and along with Broccoli and Michael Wilson decided to explore a more intimate story in For Your Eyes Only. This one would jettison enormous sets, endless action sequences, gadgets, and return Bond to his roots as a resourceful and opportunistic agent.

As the Eighties dawned, the edict for this new decade was to bring Bond back to basics. With Moonraker’s excesses, it was felt to pursue that approach any further would be a slippery slope indeed. John Glen, another long time Bond editor, took the director’s reigns and along with Broccoli and Michael Wilson decided to explore a more intimate story in For Your Eyes Only. This one would jettison enormous sets, endless action sequences, gadgets, and return Bond to his roots as a resourceful and opportunistic agent.

For the first time there was some doubt in Moore’s returning to the role, and actors like Michael Billington, Lewis Collins, and Michael Jayston were tested. The somewhat lower key opening was in fact a remaining style choice in the event this would introduce a new Bond. But, having turned Bond’s fortunes around in the Seventies, the producers were reluctant to begin a new decade without their lucky charm, and Moore returned to portray 007.

This is the film where Moore is closest to Fleming’s interpretation of the character. In a scene where Bond has a bad guy dangling in a car off the edge of a cliff, he helps the vehicle on its way with a kick, sending his adversary to his demise. Moore was reluctant to play his version of Bond this way, but the producers prevailed, and some argue for the first time his James Bond appealed all the more showing a little shadow with his light. With the theme of vengeance prevalent instead of some megalomaniac trying to rule the globe, this film also proved Moore was capable of more than just sardonic quips and a raised eyebrow.

Sadly, Bernard Lee, who had played M for 11 Bond films, died in January of 1981, before he could shoot his intended scenes. As a sign of respect, the role was not recast and M was written out for this adventure.

This film would mark the first time the recording artist of the title song would appear during the title sequence of a Bond movie; Sheena Easton sang her way through it after Blondie refused an offer to do it. The last film to be solely released by United Artists (who merged with MGM soon after) would ultimately go on to gross 195 million dollars at the box office. Reviews were at times scathing for the film, with some calling it bland and forgettable; even Moore was starting to receive his fair share of negativity with critics, and it is this film that had some starting to take note of Moore’s advancing years. Retrospectively, many suggest this to be the closest to Connery’s incarnation, performance-wise, that Moore ever got.

1983 would see Eon face their most direct threat from the Kevin McClory rights issues, when he managed not only to get a competing Bond film up and running, but secured Sean Connery to again play James Bond after 12 years. Roger Moore wasn’t at all enthused to return this time out, and before McClory’s announcement, the producers were actively and publically searching for who would become the next 007. Timothy Dalton’s name again popped up, but again timing wouldn’t permit it, and American James Brolin this time became the frontrunner for the role. After the announcement of the Connery starring Never Say Never Again, a remake of Thunderball essentially, Broccoli felt it an unwise gamble to do Octopussy without Moore. Would he be proven right?

Robert Lee would become the new M, The Spy Who Loved Me’s Maud Adams would return as the titular character after Faye Dunaway became too expensive for the producer’s tastes, and Desmond Llewelyn’s Q would be given a far larger role than usual. Shot primarily in India, the film would see Bond uncovering a plot to disarm Europe with a nuclear weapon.

As with all of Moore’s Eighties Bond films, this one continued its back to basics approach, but with scenes like Bond dressed as a clown, in a gorilla suit, and warbling a Tarzan like cry as he swung through the trees, some felt his Bond was at odds with the style they were attempting. Unlike his Seventies entries, where the outlandish sets, stunts, and plots seemed to fit Moore’s approach to the character well, the Eighties entries tried to rely more on hand-to-hand combat, opportunistic behaviour, and less gadgetry—Moore’s weakest areas. When delivering double entendre, pithy comebacks, and schmoozing with the elite, nobody does it better. But Moore was now in his fifties, and trying to convince as a man in his physical prime, fighting bad guys or wooing women half his age, was not ringing true anymore.

Reviews again were not favourable, with critics starting to believe Moore and the Eon producers were demeaning Bond and failing to honour his past legacy. Nevertheless, Broccoli’s choice to keep Moore in the role proved to be the right one—financially at least. Octopussy did in fact beat Connery’s Never Say Never Again marginally, taking 187 million dollars.

“I was only about four hundred years too old for the part.” –Roger Moore, on A View to a Kill, 1985.

The fourteenth Bond entry would be Roger Moore’s last, and, although the last three had him doubting his relevance in the part, it is only A View to a Kill that he truly regretted returning for.

Honing in on the burgeoning microchip industry, the story this time would follow a psychopathic American businessman who wants to wipe out Silicon Valley and create a monopoly in his favour. Spanning England, France, Iceland, Switzerland, and America, this last Moore outing would be a true globetrotter. Sting and David Bowie were contenders for the role of the main villain before Christopher Walken was secured; Grace Jones’ flamboyance was added to the mix as henchman Mayday; this would be the last film for the original Moneypenny, Lois Maxwell; and Maud Adams, who was visiting Moore on set, makes an uncredited cameo in her third Bond film.

Some have commented Moore was looking leaner and fitter than he had in years for this outing, but at 58 years old his believability in the role was no longer adequate. Audiences and critics alike were weary of watching him gallivant about like he was 20 years younger, and with nothing in the story acknowledging the passage of time, A View to a Kill was savaged when it was released in 1985. It is widely regarded as one of, if not the, worst Bond film ever made. The only one to come away with anything resembling a compliment from the film was Christopher Walken.

Some have commented Moore was looking leaner and fitter than he had in years for this outing, but at 58 years old his believability in the role was no longer adequate. Audiences and critics alike were weary of watching him gallivant about like he was 20 years younger, and with nothing in the story acknowledging the passage of time, A View to a Kill was savaged when it was released in 1985. It is widely regarded as one of, if not the, worst Bond film ever made. The only one to come away with anything resembling a compliment from the film was Christopher Walken.

Even with a respectable box office of 150 million dollars, Eon was being accused of not even trying anymore. The writing was on the wall for all to see: the Moore era was over.

Whether you prefer your Bond with a little more tooth, like the classic early version or the current incarnation, Roger Moore consistently rates as the most beloved 007. To Moore, he could never embody the cold-blooded killer aspect that Connery did so well, and found the notion of a man with a gun as a hero to be preposterous. His choice was to embrace the ludicrous in Bond and just have fun with it. He didn’t want to take Bond seriously, and subsequently never asked his audience to. But by the time he left the role, his interpretation had long since outstayed its welcome. There is no doubt in anybody’s mind that Moore saved James Bond. In the early Seventies, with so much indecision and change surrounding the series, it was believed by most to be the end for 007. Moore’s tenure in the role promised stability, endurance, and box office clout. It was him that cemented the idea in audiences’ minds that James Bond could change faces and endure, and it is that remarkable accomplishment that is Roger Moore’s legacy to the series. Moore was the gentleman spy, the lethal jester, the lighter Bond. He may regret staying on so long, but there is no doubt that he was beloved, and for many—missed.

Check out part one of the Bond series - Bond: The Connery Era - (1962-1967, 1971)

Check out part two of the Bond series - Bond: The Lazenby Year

Check out part four of the Bond series - Bond: The Dalton Era (1987-1989)

Check out part five of the Bond series - Bond: The Brosnan Era (1995-2002)

Check out part six of the Bond series - Bond: The Craig Era (2006- )

Also, don't miss our review of Bond 50, the massive set of all 23 James Bond movies meticulously remastered on blu-ray.