With Alien: Covenant having hit screens in 2017, we thought we’d take a trip back and explore one of the most successful and often turbulent franchises in cinema history. This six part article series will take you from the beginning, through all the twists and turns, all the way through to Ridley Scott’s latest entry into the Alien legacy.

Part 4

Also read:

The Alien Franchise: The Ripley Saga Pt. 1

The Alien Franchise: The Ripley Saga Pt. 2

The Alien Franchise: The Ripley Saga Pt. 3

ALIEN Resurrection (1997)

ALIEN Resurrection (1997)

After the disastrous production of Alien 3, and the lukewarm to hostile reception worldwide of the finished product, there was absolutely no one previously involved that was in a hurry to do another one.

Brandywine was especially vocal with Fox about their opinion that to continue on would ruin the franchise and fought to stop it, refusing to work on another. Ripley was dead, and there it should end was the Brandywine consensus. Not even their star, Weaver, was interested, assuming she had put Ripley behind her. But studios don’t let their franchises stay dormant for too long. Alien 3 may have gone down like a turd sandwich with audiences, but it had made triple its budget back at the box office, and that at the end of the day is all the motivation 20th Century Fox would need.

Joss Whedon was a then relatively unknown screenwriter who had cut his teeth on sitcoms like Roseanne and Parenthood. But he had started to appear on Hollywood’s radar for recent script doctoring work on The Getaway (which was a project Brandywine’s Walter Hill was involved in) and especially Speed, a huge hit for Fox. It was decided that he would be the guy to write the next Alien instalment. New producer Bill Badalato set him to task.

The brief Whedon was given was to start with a clone of the Newt character from Aliens and he dutifully handed them a 30 page treatment outlining this idea. As with every film before it, the many cooks at the studio suddenly changed their minds on the direction; and after strong influence from Brandywine (who opposed even the idea of another film) the studio decreed that Ripley was the franchise’s anchor and instructed Whedon to write her back in. This, according to Whedon, was a tough ask, but eventually he devised what would be a clone/hybrid of Ripley, made in a lab hundreds of years after Ellen Ripley’s heroic demise. Now keep in mind, Weaver was not on board as he toiled away on this version.

But as luck would have it — or perhaps the cynical might pay due consideration to Fox’s big fat cheque book — Weaver liked the script, liked the 11 million dollar pay day offered, and became a co-producer. Weaver has gone on to state that what appealed about Whedon’s script was the opportunity to play a different kind of character, a blend of Ripley with this new predatory facet to her. It was the opportunity to do something fresh in her eyes that convinced her to come back.

As with previous films, many directors were either considered or courted. Danny Boyle became the first man approached, and it went as far as Boyle meeting with the effects supervisors (returning from Alien 3) to discuss things, but ultimately was not interested in proceeding. Peter Jackson, just a few years away from his Lord of the Rings triumph, was also asked, but immediately declined. And hot off another Fox hit, The Usual Suspects, Bryan Singer was another young director courted by the studio.

Jean-Pierre Juenet

Having no luck closer to home, Fox cast the net wide — all the way to France. Based on his recently completed script Amelie, Jean-Pierre Juenet was their man. Surprised by even the offer, Juenet quickly warmed to the idea of directed in his words ‘a Hollywood movie’.

He had been a package deal with renowned French conceptual artist Marc Caro, but Caro quickly dismissed the idea of participating, not wanting to bend to the American studio system. Juenet had a more pragmatic ideology. With a 70 million dollar budget he felt he had the scope to take himself to school, as it were, on how to make a commercial, contemporary American studio movie. While reworking the script with Whedon, Juenet watched the previous entries and modern films of the time, read the production records, even listing the amount of shots and camera set-ups to prepare himself meticulously to be able to shoot the kind of movie the studio would require. Caro visited briefly and for their friendship did some brief costume sketches which would later be refined by Bob Ringwood.

The studio had somewhat of a godsend in Juenet, at least in that they had a hungry director with a clear vision but also a very level temperament for the business end of making this movie. It would not be all smooth sailing, but the director would by and large do what he could to accommodate their interests and well as his own.

Genre Performers Fall In

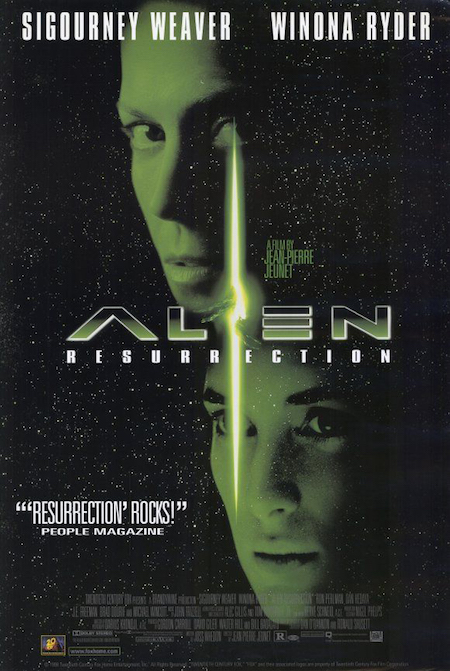

The cast filled with genre performers such as Michael Wincott and Brad Dourif. Dan Hedaya signed on to play a general. Gary Dourdan, a few years off CSI fame, made an early appearance. The indelible Ron Perlman played Johner, an archetypal misanthrope the actor could do in his sleep. French actor Dominique Pinon would play paraplegic mechanic Vriess, and rounding out a stellar cast would be then ‘it girl’ Winona Ryder as Call, a character that ends up being revealed as the android of the piece.

Production hurdles from this film seem anaemic compared to the last three but there were a few challenges to overcome. The first was Weaver’s demand the film be shot in Los Angeles, as she felt that the cast and crews from previous instalments had been exhausted by the London location of the trilogy. So Fox acquiesced, constructing a 36 by 45 metre tank in house at their studios, to facilitate the underwater scenes the script required.

As a result, Ryder’s near drowning at a young age proved to be a big sticking point with the actress when it came to filming those scenes. The entire main cast were required to train and be able swim, and despite her suggestion that a body double be used, she was made toe the line with the rest of the cast. To her credit, despite severe anxiety, she pulled it off.

Weaver became insistent that in a scene where the Ripley clone is playing basketball, she tosses the ball nonchalantly over her shoulder back to the basket and gets it in flawlessly for real. The shot was important in the director’s mind to show Ripley’s new abilities but he was happy to do it with CGI. As they burned through the production day and copious amounts of film, Weaver just couldn’t get it and allegedly nerves were starting to fray. The crew were ready to call it a day, but Weaver gave it one last try and pulled it off. Ron Perlman was so excited he broke character, and if not for the sheer shock of it finally happening, his delayed elation would have rendered the shot redundant. Jeunet upon reviewing the shot, noted that the basketball goes out of frame briefly and offered to cgi that frame or two away. Weaver steadfastly refused and the shot remained. What had become an urban legend is that she got it in one take. Sorry to disappoint.

The next conflict was between Fox and Jeunet. The director had insisted in the design of the hybrid alien that it have some twisted looking genitalia, consisting of male and female parts. Uncomfortable with this design Fox pushed and pushed but on this Jeunet remained adamant… Until, that is, he saw it closer to completion of the edit and decided that “it was too much, even for a Frenchman.”

Blue Sky Studios

Blue Sky Studios were brought on board to have the distinction of creating the first CGI aliens in the franchise’s history. They were required to create between 30-40 wide shots of the creatures, because Jeanet thought it was easier to tell it was a man in a suit when the whole alien could be seen. They also helped removed the hybrid’s genitalia.

Miniature modeller Nigel Phelps also met with a last minute blow when his design for the USM Auriga was rejected three days before it had to be finalised. Jim Martin and Slyvain Depretz were quickly brought in to join Phelps for a redesign, which also didn’t go smoothly until Depretz’s design was chosen.

Composer John Frizzell came to score the film by way of recommendation from a friend. When he score the gig, with music demos from The Empty Mirror, he ended up spending several months and composing several scores until Jeanet approved it.

A Divisive Audience

When Alien Resurrection finally hit screens in 1997 it was met with a divisive audience, both from fans and critics. Roger Ebert famously called it one of the worst films of 97. It didn’t completely tank, bringing in just north of 161 million at the box office, most of it from overseas markets.

This reviewer sees many merits within its narrative. There is certainly an abundance of fine craftsmanship and some pretty compelling performances. It certainly achieves Jeanet’s intention of bringing something different to the screen. But what it failed to do was thrill or terrify. Interesting is the nicest adjective one could use to describe this entry.

Joss Whedon has come out since and publically stated his dissatisfaction with the final product. Some critics blame his script solely. Giger called it ‘and excellent film’ but also made it know he was pissed about not being credited. No one seems to be able to agree.

It is a shame really, as for the first time in the franchise’s history production did not resemble to pantheon of studio interference and a director of considerable talent was let do his job. Unfortunately, compared to the three men he followed, Jean-Pierre Jeunet is the weakest director of the original run of films. Perhaps stroke inducing stress and studio meddling against men of unprecedented talent is what gave us these wonderful films?

Also read:

The Alien Franchise: The Ripley Saga Pt. 1

The Alien Franchise: The Ripley Saga Pt. 2

The Alien Franchise: The Ripley Saga Pt. 3